Content note: discussion (and non-explicit visuals) of sexual violence, rape apology.

The internet has been somewhat crazy of late because a man wore a sexist shirt while being interviewed on TV, was called out on it, and subsequently apologised. It all wouldn’t have been such a big deal, really, except that all of a sudden feminism was being charged with obliterating a man’s scientific achievements and censoring artistic expression. Or so the media circus went.

I have been travelling lately, around Italy, and as such I have been in a lot of museums and galleries. I mainly went to these places to see the Roman collections, as I don’t pretend to be very interested or knowledgeable about art in general. But I also dropped in on a few other exhibitions, to see the sort of things generally seen as part of the canon of the Western artistic tradition, the masters, if you will.

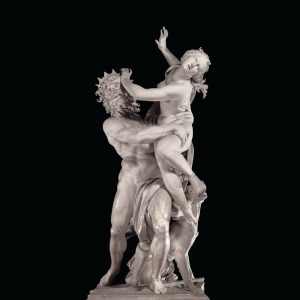

Turns out, the masters seemed to be fascinated with rape, especially scenes of rape from Classical myth. Proserpina, the Sabines, Lucretia. On more than one occasion, I wished I’d brought along a pen and paper so I could make little placards to stick next to the paintings and sculptures. ‘Warning,’ they would have said, ‘this piece contains scenes of violence against women.’ I wonder if that would have caused a similar media circus to shirtgate.

Because that’s what it is, even if we never speak about it and, perhaps, don’t want to think about it. It is, after all, art, and art should answer to no-one – or so the rhetoric goes. To problematise it would be to spoil its beauty and de-value the skill of the artist.

But why is art so seemingly immune? Why is it that we talk about Bernini’s sculpture of the rape of Proserpina in terms of its extreme beauty and emotion and skill, but never in terms of its horrific theme? It’s certainly not something the audio guide commentary at the Villa Borghese will point out to you. Or this art zine, which waxes on about the ‘exquisite beauty’ of the rape. Why do we admire the craftsmanship of Giambologna’s sculpture of two men holding down a Sabine woman who is trying to flee and call it beautiful? (And why do websites on the sculpture like this one make sure to say that ‘rape’ is a mistranslation – when it isn’t necessarily.) Why do we choose to adorn the walls of galleries and palazzos with paintings of a crowd of men raping a woman without ever seeming to acknowledge what is actually happening in these scenes, without wondering why exactly we want to look at it?

Why is rape in art beautiful? I probably couldn’t argue with the fact that many of these pieces are incredibly skilfully produced. The expressions of terror and desperation on the women’s faces are as masterful as they are utterly disturbing. (At least no-one could say they actually wanted it.) But the works also seem exploitative and sensualised. The entire bodies of Proserpina and the Sabine woman are on display: they are naked, their breasts are carefully exposed and turned towards the viewer, the male hands that claw at their bodies draw attention to their butts, so detailed that you can see their fingers sinking into soft flesh. In Belluci’s Rape of Lucretia, her entire body is exposed towards the viewer while her rapist remains fully clothed. In the paintings, the women at least retain some of their clothing, but as they try to evade their rapists their breasts are provocatively exposed and he curves of their bodies emphasised. Proserpina in Giordano’s painting keeps a little more of her body covered, but her nakedness is still on display for everyone while the rest of the figures (except for the weird flying thing above her, also female-bodied) retain their clothing.

They are not sympathetic portrayals, but exploitative and voyeuristic ones. The focus is not on their fear or their situation, but on their bodies. Yet they are accepted as great art, because they are old and because they are part of a canon, and probably because they are women from myth and not everyday life. They are not problematised, but accepted as beautiful. They are great art rather than depictions of violence.

Of course, I accept that you can’t simply say that art should never display violence, or even sexual violence and rape. Violent art has, I think, the capacity to challenge the way we think about the things that happen in the present and have happened in the past. For me, great art is about exactly that: it is not only about the technical skill that has gone into a piece, but about the ability of a piece to make you think and feel in a way you might not have expected.

But I don’t think I can see that in the scenes of rape I’ve seen in some of the greatest art galleries in Italy. The depictions strike me as passive, as accepting the way that our patriarchal society has traditionally thought about women’s agency and women’s bodies rather than challenging it or providing a new perspective. To me personally, that makes it not great art. And even if the rest of the world disagrees with me, it’s still not immune to criticism, however seminal or masterly it is described in a guidebook. Just as a man wearing a shirt with sexualised cartoon women in bondage gear isn’t immune because it’s ‘art.’

You sort of answer your own question. It isnt the “rape” that is celebrated as beautiful its the technique an detail that is celebrated.

Good points, Jo. We did Ancient Rome in Year 11 and Pompeii in Year 12, as well as read and heard other things since. The Romans were about power. They were about power against their conquests, and that included women.

For example, the Ancient Romans are attributed for prostitution and lack of social norms that were enforced when Christianity became the State religion. What is not talked about enough, I don’t think, is that sex in Ancient Roman times were all about power for the most part. Going back to prostitution, most Roman women actually didn’t participate in prostitution, only slaves and migrants (women that were trafficked?), usually from Africa or the Middle East. I can see a great power imbalance, can’t you?

Ancient art is fascinating. However, I think it’s hazardous to celebrate art and such a culture without critically looking at the context.

Incidentally I was also recently in Italy. And though I wasn’t there to tour, I did see a bit of art (mostly 19th century). My primary reaction was, “Wow, take a look at all that colonialism!” *snap snap* “What a great study of rigid gender roles!” *snap snap*

I think the most important thing to understand is that the artists’ intentions do not control the meaning of the work. Those artists likely wanted to glorify mythological tales of rape (or the colonization of Mexico), but that’s no longer the meaning of the art. Now the art is a monument to past eras with very skewed moral standards.

The idea that “artistic expression” is something that should not be criticized is very strange. Criticism is a fundamental part of living art. I think we are so used to “dead” art, the criticism of which seems inaccessible to most of the public.

I wonder if it is because sex was taboo in the literature of the time (as far as I know) and if they wanted to paint something that showed the woman’s form or a sex act from literature (so it would be classed as art rather than pornography) they used the scenes they had.